La ceremonia de Cha Chaak, registrado por el inglés Thomas Gann en 1915 en un pueblo en el norte de Belize, es la primera ceremonia registrado, y tan bien que merece mayor conocimiento. Como hoy es difícil encontrar, la reproducimos en lo siguiente.

Proceedings of the Nineteenth

International Congress of Americanists Washington, December 27-31, 1915.

Published 1917

The Chachac or rain ceremony, as practised by the maya of southern Yucatan and northern British Honduras

By Thomas Gann

The Santa Cruz and Icaiché, or Chichanhá, Indians occupy today the southern portion of Yucatan, and many of them are scattered throughout the northern part of British Honduras. The Santa Cruz were estimated by Sapper at from 8,000 to 10,000, and the Icaiché at about 500. At the present time Santa Cruz probably number fewer than 5,000, whilst the Icaiche have dwindled to under 200, many of both tribes having migrated into British Honduras and Guatemala, when garrisons were placed, by the Mexican government, at Bacalar, Santa Cruz, and Ascención Bay. It is difficult to estimate the exact number of pure Indians in British Honduras, as they are mixed, in the census returns, with Yucatecan mestizos.

These tribes occupy an intermediate position between the civilized Maya or northern Yucatan, who have lost most of the traditions of their former civilization. and the Lacandones of the Usumasintla valley who, of any of the Maya tribes, having come least in contact with outside influences, still retain unaltered many of their ancient religious observances. Their religion is superficially Catholic; fundamentally however it is probably much the same as that of their forefathers before the coming of the Spaniards, though one may live amongst them and even come into close contact with them for years, without suspecting that they are not orthodox Catholics. Their ritual at the present time consists of a curious grafting of the Roman Catholic ritual on that of their ancient religion; for as will be seen, St Lawrence, Santa Clara, the Sun God, and the Rain God, may all be invoked in the same prayer, whilst in all the ceremonies the cross has been substituted for the Images of the old gods, though many of the latter are invoked by name, and the ceremonial procedures and offerings have altered little, if at all, since the conquest.

Closely associated with primitive agriculture of these tribes are four principal ceremonies. The first of these takes place at the cutting of the bush to make the milpa, the second at the planting of the corn, the third whilst the corn is growing, and the fourth at the harvest. Of these, the third, known as the Chachac, the object of which is to obtain rain, and the last, known as the Hanel-kol, a kind of harvest thanksgiving, are the most important. Only the Chachac ceremony will be described in detail, as all the others resemble it closely. The ritual is that of the Santa Cruz, but this differs very slightly from that of the Icaiche or Chichanha, and where such differences exist they are pointed out.

The ceremony was performed at the plantation of a Santa Cruz Indian who had settled in British Honduras, early in the month of June, 1915, when rain was much needed for the maize crop, It commenced at 9 a. m. and lasted until 6 p. m. All the previous night the women of the family had been busy grinding corn to make masa, and pumpkin seed to make sikil, for the ceremony. The previous day the men of the family had prepared the pib, an oblong hole in the ground, 4 feet by 2 feet, by about 2 feet deep, in which to cook the various com binations of sikil and masa, piling by the side of it a heap of small blocks of limestone.

Very early in the morning of the day the priest arrived with his assistant at the milpero’s house. Both were dressed in clean cotton trousers and shirt. the latter hanging outside the trousers, with sandals on their feet. This man called himself a men, but was called by the owner of the milpa a chac, whilst the Chich anhá priest called himself an ahkin (Ahkin was the ancient designation for priest also). They chose a site, under some tall timber, about a quarter of a mile from the house. Here they thoroughly cleaned from underbrush, a circkel feet in diameter. In the center of this they proceeded, with the help of the male members of the family, to erect a rough hut, 12 feet square, with sloping roof 7 feet high in front, 5 feet behind, open on all sides, and built of freshly cut sticks, the roof being of huano, or palm-leaf, also freshly cut.

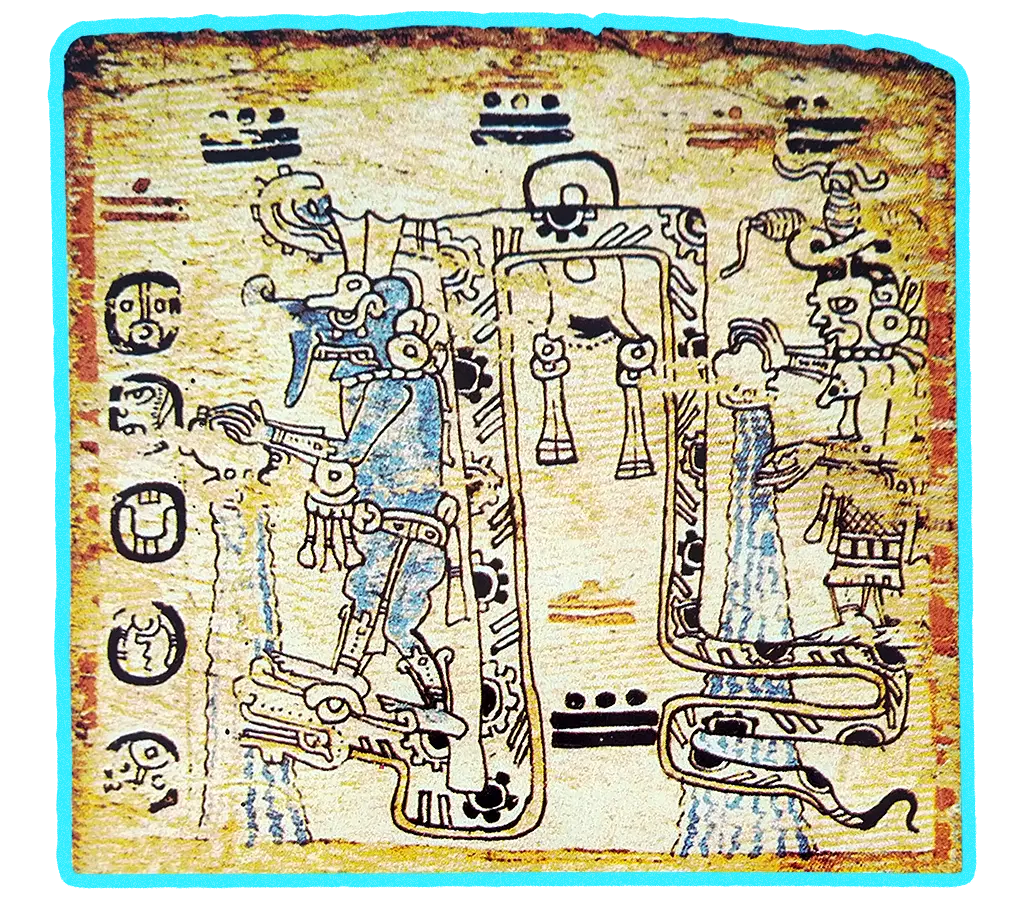

By the side of this was constructed a smaller hut, 6 feet square, the floor of which was covered with several layers of newly cut wild-plantaín leaf. Within the large hut the priest next proceeded to erect a table, or altar, 6 feet by 4 feet and 4 feet high. For this four sticks with forked tops were first firmly fixed at the four angles, cross-pieces were laid in the crotches, and these supported long which formed the top of the altar, the whole being bound firmly together with bejuco (fig. 1). The central four feet of the altar was next roofed in with an arch of freshly-nil branches of a bush cal1ed Jabin, with the smal1 green leaves still attached. About a dozen chuyubs were now prepared and placed on the altar, under the arch. These chuyubs are rings, 4 to 6 inches in diameter, made of strands of bejuco, bound together with fibers of palm-leaf, and used to support small calabashes. To the right of the main shed was next at tached a string of henequen. about 8 feet long, tied at its other end to a post in the ground; upon this were suspended three chuyubs each holding a calabash. ( See fig. 2.)

The masa ground by the women was now brought out in four huge calabashes, two of which were placed on the altar to the left and right of the arch, and two beneath; all were covered with clean cotton cloths. With these were a jar of balché, a jar of water, and a large calabash of sikil, all covered with wild-plantain leaves, which were also placed beneath the altar. Beside the balché jar were placed strings of the bark used in preparing the drink. Beneath the three suspended chuyubs was a small wooden table, upon whuich were placed piles of tortillas, and calashes of masda, and water, all covered with a clean cloth.

Everything was now ready for the ceremony to commence. It may be pointed out that the palm-thatched huts are not absolutely essential, for when the ceremony was performed by a Chichanha Indian, the altar was covered only by the arch of jabin, whilst the carpet of wild-plantain leaves at the side of the altar was uncovered. It is absolutely essential that everything used in this ceremony be freshly made. The sticks and palmleaves are freshly cut, as are also the bejuco and the jabin; the calabashes are new ones, and the masa, or maize paste, sikil, sachab, and balche, are all freshly made. The calabashes of masa from the altar, and beneath it, were taken to the small shed, where a number of palm-leaves (le-haz) and squares of wild-plantain leaf (Ie-chit) had been prepared. A palm-leaf was placed upon the ground and covered with several squares of plantain-leaf; the priest, his assistant, and several of the older male members of the family each took a piece of masa, about the size of a cricket-ball; the priest flattened his ball out into a sort of thick tortilla upon the plantain-leaf: over this was poured a little sikil; the next man flattened his hall of masa on top of this, over which another layer of sikil was poured, till there were from five to thirteen layers in all. The priest next indented, on the top layer, a cross surrounded by a number of holes (fig. 3); these he filled with balche. (A thin yellowish, slightly intoxicating liquor, made of fermented honey and water, in which strips of bark have been steeped ). When the balche had sunk into the mass he filled both holes and cross with sikil, and tied the whole up in palm-leaf, which was again bound outside with fibers of split palm-leaf. The complete cake, called tutina, was placed at the right side of the priest. The greatest number of layers allowed in each tutina is thirteen, the smallest five. This priest says he makes all numbers but ten and his first five tutina were composed of thirtheen. twelve, eleven, nine, and eight layers respectively. There is no limit to the number of tutina made, but it is absolutely essential that all the masa be used up, in one way or another, and the amount of this is usually gauged by the number of participants in the ceremony. When ground calabash seeds are not available, a paste made from ground black beans is substituted; the cvakes made from this are called bulina (bul, bean; na. bread). All the tutina being complete, the priest: took a handful of masa ahout the size of a tennis-ball; in this he made a cup-shaped depression. which he filled with sikil, covering it over again with masa, so as to leave a core of sikil in the ball of j masa. He made thirteen of these balls called yokua, each one being wrapped in a plaintain-leaf when completed (fig. 4). When all were ready they were placed together on a large palm-leaf, firmly tied up into a bundle, called tepbil, with palm-leaf fiber, and placed with the tulina. Two more tulina were next made and placed with the others; lastly, all the sikil which remained over (about a quart) was mixed with all the masa that remained (about two gallons), and the whole well kneaded into a dough, with two or three ounces of rock-salt. This mass was divided into two pieces, each being placed on a large palm-leaf covered with plantain-leaf squares, tied up firmly, and placed with the tutina and tepbil. Whilst the priest was busy with the masa, some members of the ‘family had filled the pib with dry branches, to well above the ground-level, over which they placed a layer of the limestone blocks, which had been collected the previous day, and set fire to the wood. The priest next made a large calabash full of posol (Maya, sacha), a whitish liquid composed of honey, masa, ground parched corn, and water, with which he filled the little calabashes on the altar, as well as the three suspended in chuyubs to the right of the shed. These, he explained, were for the tuyun pishan, or solnary souls, though no such offering was made by the Chichanha priest in performing the same ceremony. Four live fowls and a turkey were next placed in front of the altar, by the assistant, whilst the priest lighted a long candle of wild-bee’s wax from a piece of glowing wood, which he placed on the left of the altar. The candle must on no account be lighted with a match; a piece of glowing wood, blown to a flame, being the only orthodox method. The priest now took up the turkey and held it by the neck, around which the assistant had placed a wreath “of jabin leaves; the assistant holding the bird’s legs, the priest poured down its throat a small quantity of balche (fig. 5), which he spooned up in a jahin leaf, murmuring meanwhile Prayer 1.

The bird was then killed by having its neck stretched by the assistant. The Chichanhá priest, when performing this part of the ceremony, himself slowly choked the bird by pressure on its windpipe, between his thumb and forefinger, murmuring Prayer I over and over again till the bird was quite dead.

Prayer I

Kin kubic ti habnal, chac yetel kichpan kolel ti San Pedro, San Pablo, San Francisco, Colebil, Bartolome.

I offer a repast to chac, and the beautiful mistress, to San Pedro, San Pablo, San Francisco, the mistress, Bartolome.

The fowls were next, one by one, treated in the same manner, and the carcasses of both turkey and fowls were removed to the house to be plucked and cooked by the women. The priest next washed his hands in the calabash of water, an act which he performed frequently throughout the entire ceremony and placing the lighted candle in the center of the altar, he turned his face to it, murmuring prayers for a few moments, in which he offered the blood of the turkey and fowls to the gods, in exchange for rain. In the meantime the various bundles of tepbil and tutina were being carried to the pib by members of the family. After being sprinkled with water, they were placed in the pib, which was now halffilled with red-hot stones and ashes; a layer of the white inner bark of the plantain being interp osed between the stones and the’ various bundles. Over the bun dles were placed more hot stones, and over these palm-leaves, with which the sides of the pib were also lined; finally, over all were raked the earthwhich had been dug up in making the pib, The priest standing in front of the altar, fac ing the east, now took a little of the sacha in a jabin leaf and slowly scattered it in three directions, murmuring Prayer II whilst doing so. The Chichanhá priest, it may be noted, scattered the sacha to the four points of the com pass. Next he took a little from two of the small calabashes upon the altar and scattered this, repeating the same prayer, afterward emptying all the small cala bashes into the large one; lastly he scattered a little from the calabashes of the tuyun pishan, and emptied them also into the large calabash, again repeating Prayer II. Small calabashes were now filled from the large one, which had been duly offered to the gods, and passed round for the participants to drink. It was most import ant that none of this sacha be left in the calabash undrunk, and none thrown away.

Prayer II

Kin kubic ti atepalob, ti noh yum, hab yetel Uahmentan, atepalob tiaca tzib nah.

I offer to the majestic ones, to the great lord (chac) honey, with corn-cake, majestic ones (the meaning of tiaca tzib nah is somewhat obscure).

During the next hour nothing was done, all sitting on the west side of the altar talking, and waiting for the contents of the pib to be cooked. When it was considered that these were ready, the priest took a small calabash of balche, and led the procession to the pib, which was opened by removing the earth, palm-leaves, and stones, till the tepbil and tutina were exposed; when the priest scattered the balche to the four corners of the pib. The boys of the family now removed the contents to the small shed, a good deal of laughter being excited by their endeavors to pick up the boiling-hot packages. On arriving at the shed, the packages were placed upon the floor, and the leaf coverings being removed, the tutina and yokua, nicely browned, crisp, and hot, were exposed; these were at once placed upon the altar, with the exception of one tutina, which was suspended to the string with the calabashes devoted to the tuyun pishim. The large cake made from the remainder of the sikil and masa was placed upon a clean cloth and crumbled into small pieces in a large calabash. A second large calabash of kool (A reddish liquid, made of water, ground corn, black pebber and achiote) was brought from the house, where it had been prepared by the women; this was well stirred, little by little, into the calabash containing the crumbled cake, by means of a small peeled wand of jabin, till the whole formed a thick paste, called sopas. Whilst this was going on, the hearts, heads, and intestines of the turkey and fowls were brought from the house, and buried in the pib, in order that no animal might eat them; which would be considered disastrous and of evil omen. The turkey and fowls, cooked and dismembered, were next brought from the house in a large calabash; the gizzarads, livers, and immature eggs were chopped into small pieces and placed on a plantain-leaf, with the legs, to which the claws were attached. The chopped parts were well mixed with the sopas, by means of the jabin wand, and a small calabash filled with this mixture into which a fowl’s leg was stuck, claw uppermost, was placed in one of the chuyubs of the tuyun pishan. The other fowls’ legs were stuck upright in the mixture, which with the rest of the fowls and turkey, wrapped in a cloth, and placed in a large calabash, was deposited upon the altar. The priest now approached the altar, where he lit another black wax candle from a smouldering stick the uncovering the balché jar he removed a little bark which still remained in it, and taking out a large calabashful, he placed it upon the altar, repeating at the same time Prayers III and IV.

Prayer III

“Ea in kichpan kolel canleoox, yetel bacan tech in kichkelem tat yum San Isidro, ah kolkal yetel bacan tech yum kankin, Culucbalech ti likin, yetel bacan in chan ttap chaac, culucbal chumuc caan ti likin, yetel bacan yum can chacoob, kin kubic yetel bacan ahtzoil atepalo,chumuc caan, yetel bacan tech in kichkelem tata Ahcanankakabool, yetel bacan tech in kichkelem tata Cakaal Uxmal, yetel bacan tech in kichpan kolel Santa Clara, yetel bacan tech in kichkelem tata yum Xualakinik, yetel bacan tech in kichpan colel Xhelik, yetel bacan tech in kichkelem tata yum San Lorenzo, yetel bacan tech in kichpan Guadelupe, yetel bacan tech Tun yum mosonikoob, meyatnateex ichil e cool cat tocah.

Kin kubic bacan leti Santo Gracia utial a nahmatcex, yetel bacan tech u nohchil Santo. Uay yokol cab halibé in yumen satesten in cipil minan a tzulpachkeex leti Santo pishan soki in mentic leti Santo promicia”.

Now, my beautiful lady of the yellow leaf breadnut, as well as you my handsome father Saint Isidro, tiller of the soil, as well as you lord sun, who are seated at the east, as well as you my small Chac, who are seated in the middle of the heavens, in the east, as well as the lord of all the Chacs. I deliver them to you with the poor servants in the middle of the heavens, as well as you my handsome father Ahcanankakabool (keeper of the woods) as well as you my handsome father Cakaal Uxmal (forest of Uxmal) as well as you my beautiful lady Santa Clara, as well as you my handsome father Xualakinik (evening breeze) as well as you my beautiful lady Xhelik (changing breeze) as well as my handsome father St. Lawrence, as well as you my beautiful lady of Guadelupe, as well as you lord whirlwind, who works within the milpa, when it is burnt.

I deliver then to you this Holy Grace, that you may taste it, and because you are the biggest saint on earth that is all my master. Pardon my sins. You have not to follow the holy souls, because I have made this offering.

Prayer IV

Kin kubic ti noh tatail, ti u cahil San Roque, u cahil Patchschacan, ti chan Zapote.

I offer these to you, great father, on behalf of your town of San Roque, your town of Patchschacan, og Chan Zapote, etc (here follows a list of villages where the priest had friends, or any interest).

The assistent next brought some burning copal of the inner bark of the plantain, and the priest taking this in his right hand waved it about for a short time, before placing it upon the altar; then dipping out a very small calabashful of balche, he scattered it in three directions, upon the ground, repeating. whilst doing so, Prayer V.

Prayer V

Noh nah ti Uxmal, ti atepalob, Ixcabach, Chen Mani, ti Xpanterashan, Cha Canchi, Cha Cantoc, Xnocachan, Xcunya, Yaxutzub, Yaxaban, ti atepalob.

Great house of Uxnal, to the majestic ones Ixcabach, Chen Mani, ti Xpanterashan, Cha Canchi, Cha Cantoc, Xnocachan, Xcunya, Yaxutzub, Yaxaban, to the majestic ones.

A very small calabash of balché was next handed round to each of the spectators, and the priest again scattered some on the ground, repeating prayer V, after which the balché was again passed. The large calabash now nearly empty, was taken by the assistant to the house for the benefit of the women. On the return of the empty calabash, the priest placed it upon the altar, refilled it from the jar, scattered some on the ground, repeating Prayer V, and again passed it round amongst the spectators, sending the little left in the calabash to the house for the women. This procedure was repeated till the jar of balche was quite empty, by which time everyone was feeling its effects. The priest next scattered a little of the sopas in four directions, scooping it up from the large calabash on the altar with one of the fowl’s claws. He then removed the calabash from the altar, and divided out the greater portion of the sopas into small calabashes, which, with a fowl’s claw for a fork, were passed round to the spectators. The little which remained in the calabash being taken to the house for the women. The priest lastly removed the tutina,yokua, and pieces of fowl and turkey from the altar, and placed them on a clean cloth, on the floor of the small shed, where he divided them amongst the male members of the family, wrapping each portion in a plantainleaf, and giving each person, at the same time, a corn-husk cigarette. This ended the ceremony, and the priest and his assistant, well filled with sopas, cheered with balche, and carrying a goodly portion of pieces of chicken and tutina, started for their homes.