La monografía etnográfica de los antropólogos Alfonso Villa Rojas y Robert Redfield sobre el pueblo de Chan Kom, cerca de Valladolid en Yucatán, realizado en 1931 solamente existe en inglés, todavía no traducido al español, a pesar de su importancia para los lectores mexicanos. En el libro se encuentra una de las primeras y más amplias descripciones de la ceremonia de Ch’a Ch’áak. Como la edición ya no se localiza fácilmente, reproducimos la descripción de la ceremonia, de las páginas 138-143, del original.

The rain ceremony

Ritual finds its most elaborate expression in the ceremony known as cha-haac (“bringrain”). The reasons why this is so have already been indicated (p. 123). The cha-chaac is not the mere periodic offering that prudence impels as are, commmonly, the u hanli col and the u hanli cabo Nor is it stimulated, as are those two ceremonies on many occasions, by anything so private and individual as one man’s sickness. The cha-chaac is performed only in response to crucial need that strikes simultaneously at everyone: the common anxiety produced by drought. Only pestilence brings about a situation that is comparable, and to combat pestilence there is another major communal ceremony (p. 175).

Therefore the cha-chaac is a ceremony in which every man in the village participates. During the period of its celebration all ordinary masculine activities cease; the en tire adult male population is gathered at the place of ceremony. Therefore, although the ritual forms used in the cha-chaac conform to the pattern represented by the u hanli col, they are cast on a larger scale. Where the other ceremonies require only a few hours, the cha-chaac demands three days; where the others demand the sacrifice of a few fowl, the cha-chaacrequires dozens, with cornmeal dough in proportion. Finally, the fact that this ceremony expresses the desire of all the participants for just one particular concrete result-the coming of rain-is ritually reflected in the mimetic representation of rainstorm which forms the central feature of the cña-chaac. During the period of these observations only one cha-chaac was performed in Chan Kom. The following account is, therefore, written in the past tense. The h-men who officiated was one who had charge of several of the variant u hanli col ceremonies just mentioned; the ritual about to be described probably includes some elements not characteristic of all cha-chaacs -notably the element of ceremonial drinking from a special homa. Some of the prayers this h-men used for the cñaachaac were identical with those which he uses habitually for the u hanli col.

The summer of 1930 was unusually dry. The people of the villages saw their entire harvest threatened by a prolonged drought. This was not the only anxiety.

The drought being merely local, much corn was growing elsewhere and the price of maize had accordingly fallen to the extraordinarily low figure of one peso a carga. An epizootic was destroying the hogs. By the middle of July the number of candles burned in the oratorio had notably increased. People were going singly to bear their individual troubles to the santo. As the dry weather was prolonged, it became more and more a subject of conversation till it absorbed other interests. Individual concerns coalesced in one great communal anxiety. The first public expression of need was a novenario held for the patron santo. Rain fell thereafter, but not in sufficient quantities to save the threatened corn, now approaching ripening. The novenario was followed by prayers to the Holy Cross and others to the Señor Dios. But the drought persisted. Then at last, at the end of August, the men of Chan Kom decided to hold the cha-chaac. A h-men of repute, from a neighboring village, was already present, summoned by one agriculturalist to perform for him the u hanli col. He was asked to take the rain ceremony in charge.

Early on the morning of the first day he erected an altar, in exactly the manner described in connection with the u hanli col, in the yard back of the cuartel (public building). More commonly the place for the cha-chaac is at a slightly greater distance from the plaza, on the outskirts of the village. The withdrawal of the men from contact with the women, which is always a part of the ceremonies over which the h-men presides, is particularly manifest in the cha-chaac. This feeling is expressed in the first collective act involved in this ceremony. At noon on this first day all the men went with the h-men to get “virgin water” from a cenote situated in the depth of the forest some kilometers from Chan Kom. Water used in preparing the foodstuffs for the other ceremonies is customarily drawn from the village cenote, but at the first hour of dawn before it has been contaminated for ritual purposes by contact with the women who there draw water for household purposes. For the cha-chaac this precaution is not sufficient and the water must come from the sacred cenote, where women are supposed never to go. The h-men tells the others that it is to this cenote that the chaacs come to fill their calabashes when they are about to water the young maize plants. The cenote can be reached only by crawling through a dark and slippery tunnel, about 30 meters in length. The difficulty of en trance, and the snake-wise movement of the torch-lit procession enhance the awesomeness of the ritual act. In the evening the men returned and hung their calabashes beside the altar.

Many of the men now swung their hammocks near the cleared space; and here it is expected they should remain till the ceremony is concluded. Once the sacred water has been brought, no one is supposed to return home. This provision assures that during the period of the ceremony no man has intercourse with a woman, a circumstance which, the h-men assures them, would pollute the sanctity of the proceedings and render them of no avail. The men spend the hours not occupied in sleeping or in actual preparations for the ritual in conversation and storytelling.

On this particular occasion, activities were resumed a little before dawn on the second day. The h-men named two of the older men as idzacs. They received and recorded in a notebook the two kilos of zaca, one-quarter kilo of sugar, and two candles which each man contributed. When these materials had been collected, the h-men prepared part of the zaca, stirring the meal into water from the calabashes. He put a large water-jar of zaca on the altar and offered “holy cold water” to the chaacs and balams. Then the idzacs divided the zaca among those present. This was the first of six times that day that this act was performed.

At about six o’clock in the morning, the h-men prepared three jars of zaca and placed them in gourd-carries (chuyub) hanging in a tree near the altar. These were offered to, respectively, San Gabriel, San Marcelino, San Cecilio, the guardians of the forest, and the zip (p. 117) who watch over the deer, asking them for” virgin animals.” The word (alak) used in the prayer is that reserved for tamed or domesticated animals; for the deer are the domestic animals, or familiars, of these deities. The prayers ask “that the zips may not warn the deer of the approach of the hunters”-it is a prayer for success in the hunt.

After reciting it, the h-men went to the altar and consulted his zaztuns. By looking into these small bits of translucent stone or glass, the h-men professes to learn the wishes of the gods. On this occasion he announced that “by the will of Santos Lazaro, Jorge and Roque …( The h-men on this occasion referred to these three santos, but the others previously mencioned are generaIly regarded as the guardian! of the deer.)… you will kill two deer over toward X-Cocail.” The prophecy was received with shouts of delight, and the hunters made off through the bush. At about eleven o’clock they returned, sweaty and weary, and without any deer. The h-men explained that probably the zip had protected the deer, but that they would be found in the direction of Tzeal. Zaca was again offered to the yuntzilob and thereafter the hunt was resumed, this time with more success, for the hunters got a small deer in the predicted direction. The meat was cooked in an earth-oven and placed on the altar for the hunters to eat.

At three o’clock in the afternoon, at seven in the evening and twice again before two in the morning, the h-men offered zaca to the gods; as before, the meal was divided among the men and consumed. In the intervals the men amused themselves by eating toasted squash seed and telling stories.

The activities of the first two days were preliminary to the actual ceremony, which took place on the third. At dawn, after a short intermission for sleep, the h-men filled thirteen homa and two shallow gourd vessels with balche and offered it to the gods with the same prayer used on the analogous occasion in the u hanli col ceremony. Then he called to four of the men present; these seated themselves on a bench in front of the altar and chanted a prayer to the chaacs and balams for rain. This ended, the idzacs distributed the balche among those present.

Meanwhile, inside the houses of the village, the women had been preparing the dough and the ground squash seed to be used in making the sacred breadstuffs. Morning had now come, and the idzacs received and entered in their notebooks the amounts contributed that day by each man: three kilos of dough, one-half a kilo of ground squash seed, a hen, and 75 centavos with which to buy seasonings and with which to pay the h-men.

When the hens had been collected, they were sanctified and dedicated to the gods. As described in connection with the u hanli col, the h-men put balche down the beak of each, meanwhile repeating a prayer, the idzacs wringing each fowl’s neck and then handing the h-men another. In this way twenty-three fowl were sacrificed. The prayer used here declares that there is offered to the chaacs (and to Saint Michael) a “holy virgin animal.” The prayer is in nine parts; in each of the last eight parts the h-men counted the nine times he tossed the liquor down the bird’s throat.

This proceeding consumed a considerable period of time. When it was over, the h-men returned to his hammock, and thereafter from time to time interrupted his rest to approach the altar and asperge the cross and the table with balche, to the accompaniment of the usual prayer. This he did thirteen times, and thirteen times the consecrated balche was distributed and consumed, the men returning the usual formula of thanks: “ox tezcufitabac tech, tat.”

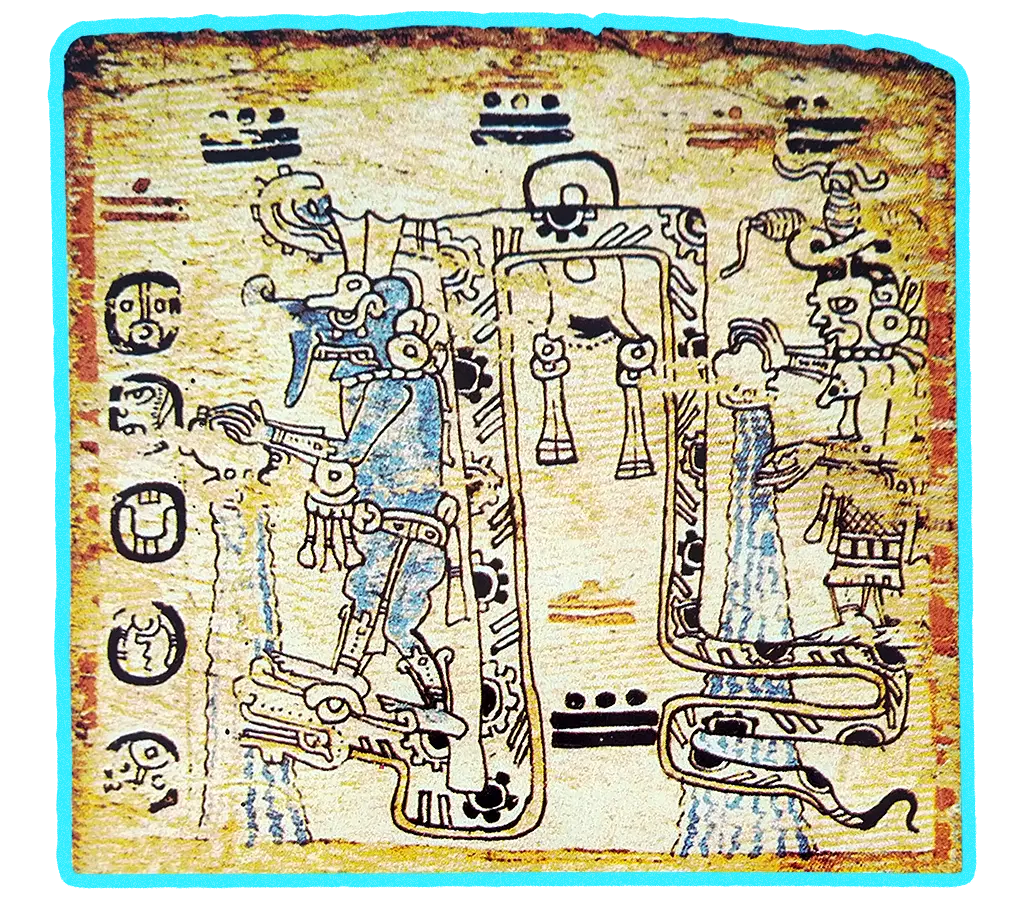

The morning was spent in the preparation of the sacred breadstuffs. These were the same as those prepared for the u hanli col ceremony, except that as this was a ceremony for the chaacs, many more yal-uah were made (this being the kind offered to these deities), and, in addition, four yaxche-uah (“ceiba-bread”) were prepared. By the time the breads were ready, it was midday and the idzacs covered the cross on the altar with branches of habin, to protect it from the rays of the sun to keep it “cold”. The breads were taken from the pib, and with the soups (prepared as described for the u hanli col) and the balche, were arranged on the altar as indicated, in the diagram

(fig. 14).

The moment had now come to deliver the feast to the gods and to make more explicit the prayer for rain. The h-men fastened four boys under the table-altar, each tied by the right foot to one post of the altar. These were the “frogs.” He then selected one of the older men to impersonate the kunku-chaac, chief of the raingods. The two idzacs and two other men lifted this man up and carried him to a specially c1eared space about 8 meters east of the altar-the “Trunk of Heaven” (chun-caan), where the kunku-chaac is thought todwell. This was done with care and reverence and in such a manner that none turned his back to the altar, for now all the yuntzilob were there gathered. An idzac supplied the impersonator with a calabash and a wooden machete. The calabash represents those used by the rain-gods in watering the corn, and the wooden knife stands for that brandished object known as lelem, with which the raingods produce the lightning. The kunku-chaac was left by himself, his bearers returning to the altar. The h-men knelt before it, with an idzac on either side, and repeated the prayer summoning the gods and invoking the various place-names of the region. As the h-men prayed, the idzacs were sprinkling the altar with balche and adding grains of incense -to a small brazier; the “frogs” were croaking a particular note special to such occasions, and the kunkuchaac from time to time rose to his feet and with his voice imitated the sound of thunder, and with his lelem the flash of lightning (Plate 13a and b).

When the prayer was over, the h-men summoned four men to help him lift the food from the altar, and he consecrated it, bit by bit,to the gods. Then (as this particular hmen was wont to do in the u hanli col ceremony), he ceremonially drank balche from a special homa covered with a cloth embroidered with a cross; and caused every man to follow him in draining a homa of balche. This ended, all went some distance from the altar, keeping complete silence so as not to interrupt the feasting of the gods, now enjoying the gracia of the tuti-uah and the kol.

When the h-men decided that the gods had finished, he ordered four men to go with him to the kunku-chaac impersonator. When they were in his presence, the hmen poured balche on his head, saying, “In the name of God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Ghost, once, twice, three times, four times, thirteen times in the name of God the Holy Ghost. Amen.”

The impersonator of the kunku-chaac then went and sat among the “frogs,” who were busy consuming the yaxche-uah. The other tuti-uah and the soups were divided among all present, and the ceremony conc1uded with the usual feast.

Afterward the h-men built one of the little racks used to make minor offerings, consisting of two horizontal poles bound to two vertical ones, and on this placed thirteen dishes of zaca, offering them to the deities with the prayer first used in the ceremony. Then, assisted by the idzacs, he took down the little altar and sanctified the place by sprinkling it with balche. This sprinkling of balche, so much used in all these agricultural ceremonies, is the device whereby things and persons are safely conveyed from the world of the secular to that of the sacred, and back again. The altar becomes a place where the gods may approach when balche is sprinkled upon it, and the fowl are consecrated to the gods by the same act. On the other hand, the place of ceremony, and the man who assumed the role of kunku-chaac, are made once more safe for the activities of ordinary life by means of this same asperging with balche.1 (1 At cha-chaacs observed at settlements near Chan Kom (X-Kopteil and Santa Maria) the mimetic representation of the gods of the rain was carried further by having four men impersonate the four chaacs of the cardinal directions. These men, each with a calabash and a machete, stood at the four corners of the altar. As the h-men murmured the prayers, the chaacs began a rude dance, movíng nine times around the altar, brandishing their machetes. This they did when the baIche was offered, again when the breadstuffs were offered. Four boys, in addition to those actining as frogs, were put in the underbrush to imitate the sounds made by chachalacas (Ortalis vetula) a bird whose cry is. supposed to presage rain. At the conclusion of these cha-chaacs, the h-men and the idzacs joined hands in a circle; every man present in turn passed inside it and was gently beaten with branches of habin, meanwhile turning around nine times.

According to men of Piste, at cha-ehaacs performed there the four impersonators of the chaacs are present (as is also the kunkuuchaae), but there is no dance around the tabIe. The h-men oSiciating at Piste is aecustomed to suspend a gourd dish ol balche above thc altar 00 a swinging mat (peten) of liana (see p. 37). To this object four cords of vine are attached, and as the dedicatory moment arrives, the four chaacs at the corners of the altar set the mat swinging, spilling the balche as symbol of rainfall.